- Story Elements

- Posts

- #001: How to Reveal A Villain

#001: How to Reveal A Villain

"Dracula" (1897) by Bram Stoker

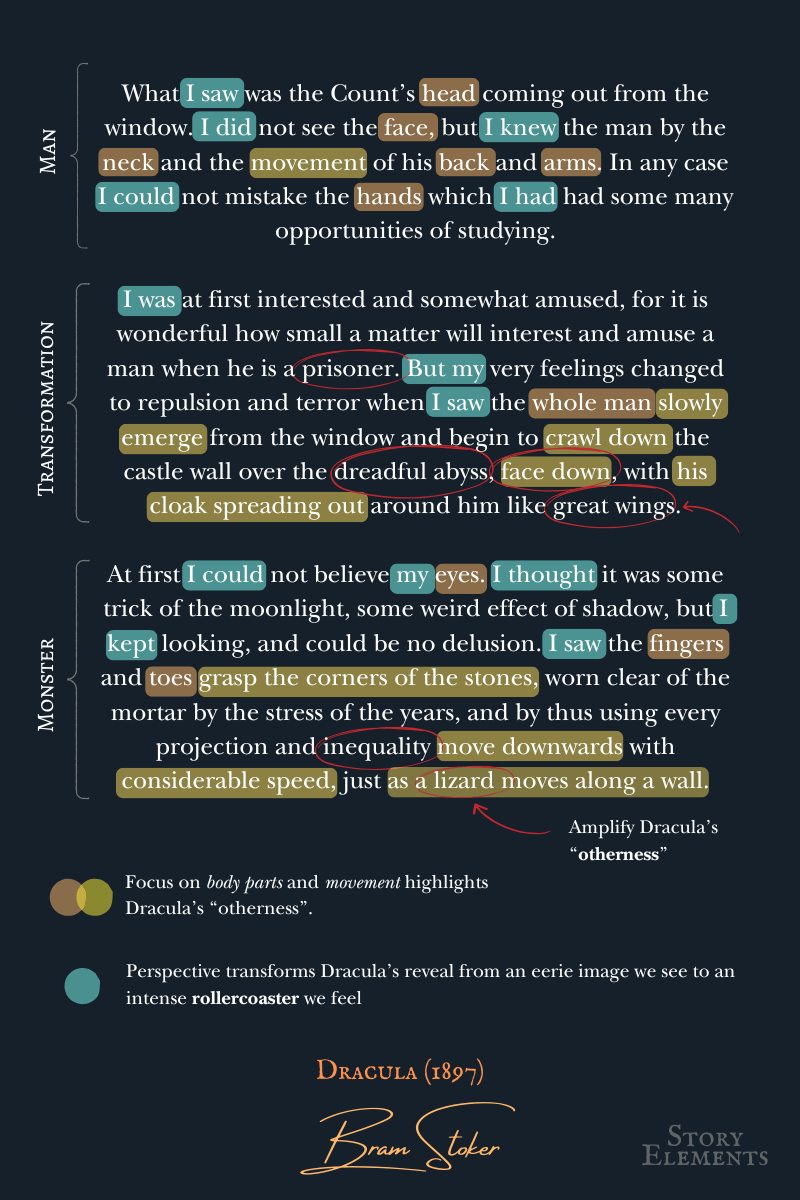

Stoker's Dracula is the gold standard for revealing a villain. One that may outlast the Count himself. How does Stoker do it? He doesn’t just announce what Dracula is, he crafts his reveal to be a rollercoaster of transformations. And he starts by placing you in the lead cart.

I saw. I did. I knew. I could. I had. I was.

With each ‘I’, Stoker locks you in the same prison Harker helplessly watches from so that you see and feel the moment Dracula, the man, transforms into Dracula, the monster.

Normally, we try to avoid overusing personal pronouns as they can create distance and make the reader feel like an outsider watching the character instead of being immersed in the story. But because Dracula is an epistolary—a story told through letters, newspaper clippings, diaries, and journal entries—we are outsiders watching the character. The result? Stoker’s use of ‘I’ doesn’t push us away. It pulls us deeper. This deep immersion is crucial because it ensures that when Harker witnesses the truth about Dracula, we don’t just see it … we experience it.

Another key to Stoker’s reveal is fixating on Dracula’s ‘otherness’. In this case, it’s the fact that while he may look like a man, he sure as hell don’t move like one. Here, Stoker plays with certainty.

By focusing on body parts, Stoker reinforces Dracula’s humanness.

Head? Check.

Face? Check.

Neck, back, and arms? Check, check, and check.

If you had any doubts about whether Dracula truly was a “whole man”, Stoker eliminates them by adding a personal insight. He notes that Harker has studied the Count’s hands, he knows exactly what he saw. And now so do we. We’re certain of it.

And that’s when Stoker truly begins the transformation. He shatters what we think we know by showing how inhuman Dracula’s movements are.

His cloak spreading out around him like great wings ….

Fingers and toes grasp the corners of the stones …

Moves downwards with considerable speed, just as a lizard moves along a wall …

Each creates a vivid image in our minds, but what really makes this scene stick is Stoker’s “positioning” of Dracula. As he crawls down the castle wall over the dreadful abyss, he faces down. Not only could no human climb this way, even if they could, they wouldn’t choose to. The psychological implications show an unnatural prowess by the Count to mock death to its face. Highlighting Dracula’s movement doesn’t just establish him as a monster, it shows his power, Harker’s inferiority, and their new dynamic: predator versus prey.

And both the Count’s and Harker’s transformations are complete.

Yet, at the story’s core, it isn’t Dracula’s ‘otherness’ that’s the most horrifying aspect and it isn’t what Stoker truly exemplifies.

The true horror of Dracula isn’t in our slow realization that he’s a monster … it’s in the instant shock of realizing that he passes as a man.

We see the same ideas in ancient myths about demons and shapeshifters and in today’s sci-fi stories with body snatchers and androids. Dracula endures today because Stoker tapped into this timeless human fear. That monsters can walk among us, undetected, right up until it’s too late.

So when you reveal your next villain, lean into their ‘otherness’. Show what separates them from everyone else, what gives them an edge and turns the dynamic into one of predator and prey. And if you can, tap into a fear that has haunted humanity forever.

Do that, and your villain won’t just haunt your readers, they’ll crawl the walls of their imagination. Forever.

Passage to Ponder: How to Present A Paradigm

Reply